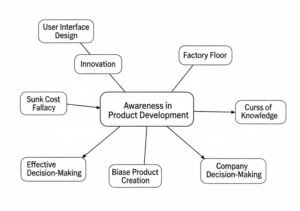

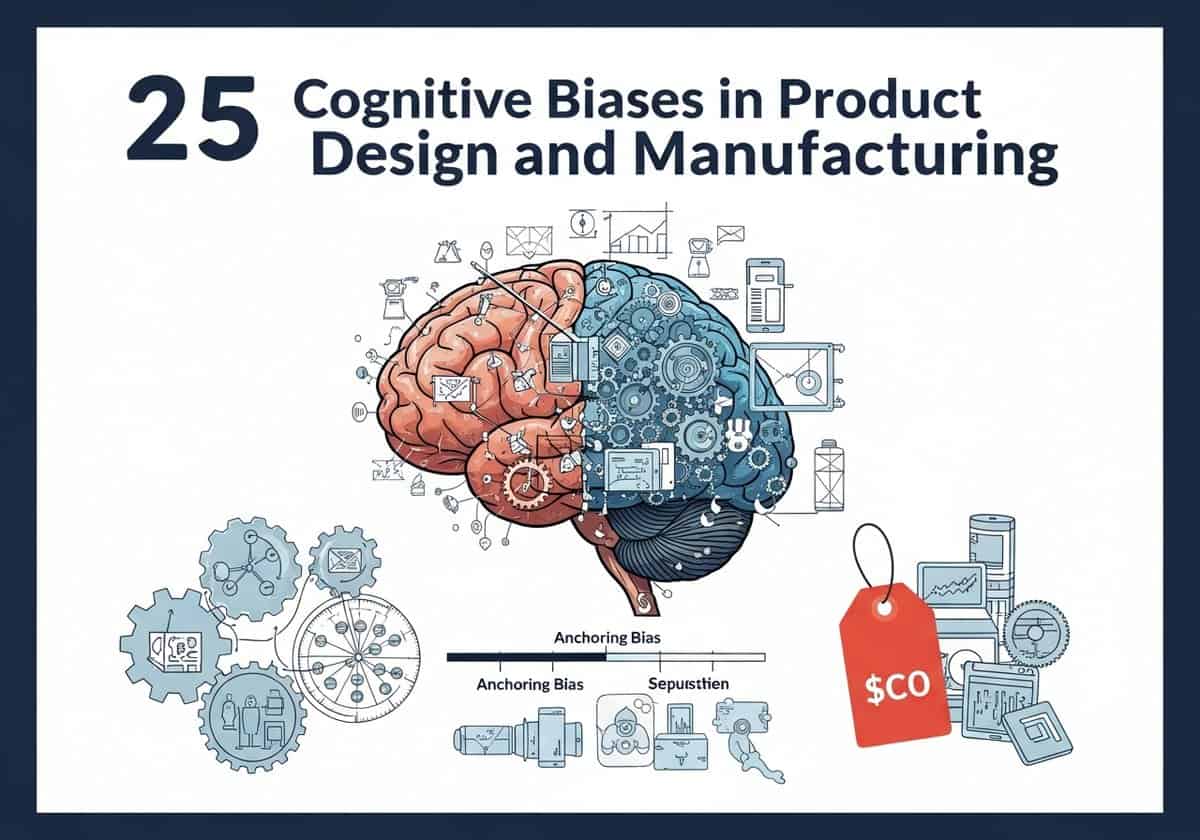

Cognitive biases are shortcuts in human thinking that shape all decisions. Product designers and engineers can improve their work by accounting for these inherent mental patterns. These shortcuts, while useful, also produce predictable, systematic errors in judgment. A working knowledge of these biases allows creators to build products that are more intuitive and successful because they align with how people’s minds actually operate.

This awareness extends beyond user interface design to the full product life-cycle, from innovation to the factory floor. The same biases that affect a consumer’s choice also influence the internal teams that develop the product and check its quality. The Sunk Cost Fallacy can trap a team in a failing project, while the Curse of Knowledge can lead an engineer to write instructions that are clear to them but confusing for a machine operator. Identifying these patterns is a tool with two functions: it informs the creation of more effective products and it refines a company’s own decision-making, cutting down on expensive mistakes.

1. The Anchoring Bias

The tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered. In product development, initial estimates for budgets, timelines, or feature scope act as powerful anchors that are difficult to adjust. A project manager’s initial “2-month” timeline, even if a rough guess, becomes the benchmark for success, constraining engineering teams and discouraging innovative but more time-consuming solutions that may emerge after the project has started.

- Abused for: negotiations, pricing strategy, and managing stakeholder expectations. A high initial asking price makes a subsequent, lower price seem like a good deal, even if it is still above market value.

- Example in R&D: an early, overly optimistic result from a single experiment can anchor an entire research project’s expectations. The R&D team and management may cling to this initial “breakthrough,” making it difficult to objectively assess subsequent, less promising data and pivot the project towards a more viable path.

2. Availability Heuristic

Overestimating the importance of information that is easily recalled. A team might over-prioritize a feature addressing a problem that a high-profile competitor recently struggled with publicly, because that failure is vivid and “available” in their minds. This can divert engineering resources from addressing less sensational, but more prevalent, issues discovered in their own user research.

- Verwendet für: Marketing Kampagnen, Nachrichtenmedien und Risikobewertung. Werbung, die auf Angst basiert, hebt oft anschauliche, aber seltene negative Veranstaltungen to sell insurance or safety products.

- Beispiel in Qualität & HerstellungEin Qualitätskontrollteam könnte anstrengende, zeitaufwändige Inspektionsverfahren für einen bestimmten Fehlertyp einführen, der vor zwei Jahren einen großen, denkwürdigen Produktrückruf verursacht hat, während es einem häufigeren, aber weniger dramatischen Qualitätsproblem, das derzeit zu größerer Kundenunzufriedenheit führt, weniger Aufmerksamkeit widmet.

3. The Bandwagon Effect

The tendency to adopt certain behaviors or beliefs because many other people are doing so.

This often drives the adoption of popular technology stacks, design systems, or project management methodologies (like a specific Agile Rahmen) without a rigorous analysis of their suitability for the specific product or team culture. An engineering lead might push for using a complex technology like Kubernetes simply because it’s what “everyone at big tech” is doing, not because the project’s scale demands it.

- Abused for: driving trends, viral marketing, and creating social proof for product adoption. It creates a “fear of missing out” (FOMO) that encourages people to join a growing movement.

- Example in innovation: an innovation department or company might feel pressured to invest heavily in Generative AI projects simply because it’s the dominant trend and competitors are all announcing their AI initiatives. This can lead to rushed, poorly conceived projects that chase the buzz rather than solving a genuine business problem.

4. The Confirmation Bias

The tendency to search for, interpret, and recall information that confirms pre-existing beliefs.

Once a team commits to a product idea, they subconsciously seek user feedback and data that validate their chosen path. During usability testing, a designer might unintentionally ask leading questions to elicit positive responses, or a project manager might highlight metrics that show progress while ignoring those that signal a flawed strategy, leading the team further down the wrong road.

- Used for: creating echo chambers in social media feeds, political messaging, and reinforcing brand loyalty by feeding customers information that confirms the wisdom of their purchase.

- Example in R&D: a scientist who believes a specific molecule is the key to a new drug may unconsciously interpret ambiguous test results as positive evidence and dismiss contradictory data as anomalies or measurement errors. This can waste significant time and resources pursuing a dead end.

5. The Curse of Knowledge

The difficulty for experts to imagine what it’s like for someone who doesn’t have their level of knowledge. This is a primary source of friction between engineering and users. Engineers, who understand the system’s architecture, may design an interface or API that is logical from a technical standpoint but completely counter-intuitive for a new user who lacks that underlying mental model, resulting in a poor on-boarding experience and high support costs. This bias is more of an inherent obstacle. It manifests in jargon-filled presentations, overly complex user manuals, and “intuitive” interfaces that are only intuitive to their creators.

- Example in manufacturing: an engineer who designs a complex new assembly machine may write operating instructions that are perfectly clear to another engineer, but incomprehensible to the floor technician who has to use and troubleshoot it daily. This leads to operator errors, reduced efficiency, and potential safety risks. A similar problem can be in the writing of the Instruction For Use (IFU) for a product.

6. The Decoy Effect

The phenomenon where people’s preference for one of two options can change when a third, asymmetrically dominated option is presented. In product strategy and project management, this can be used to guide stakeholder decisions. When presenting project roadmaps, a product manager might include a “decoy” option -one with an obviously poor balance of features versus engineering effort- to make their preferred strategic option seem more attractive and logical in comparison.

- Abused for: subscription pricing tiers and product line-ups. A “medium” popcorn is priced just slightly less than the “large,” making the large seem like a...

You have read 24% of the article. The rest is for our community. Already a member? Einloggen

(und auch um unsere Originalinhalte vor Scraping-Bots zu schützen)

Innovation.world Gemeinschaft

Anmelden oder Registrieren (100% kostenlos)

Lesen Sie den Rest dieses Artikels und alle Inhalte und Tools, die nur für Mitglieder zugänglich sind.

Nur echte Ingenieure, Hersteller, Designer und Marketingfachleute.

Kein Bot, kein Hater, kein Spammer.

Verwandte Artikel

Kontaminationskontrollstrategie und Best Practices für Reinräume 26

Von GMP zu cGMP: Der vollständige Mastering-Leitfaden

IQ OQ PQ Prozessvalidierung: Vollständige Theorie und Praxis

Die Strategien „Lone Nut“, „First Follower“ und „Fast Follower“

Die 20 besten Verwendungsmöglichkeiten von Proxies im Engineering

Wie man Eis an Eskimos Verkauft (oder Marketing-Spielereien)