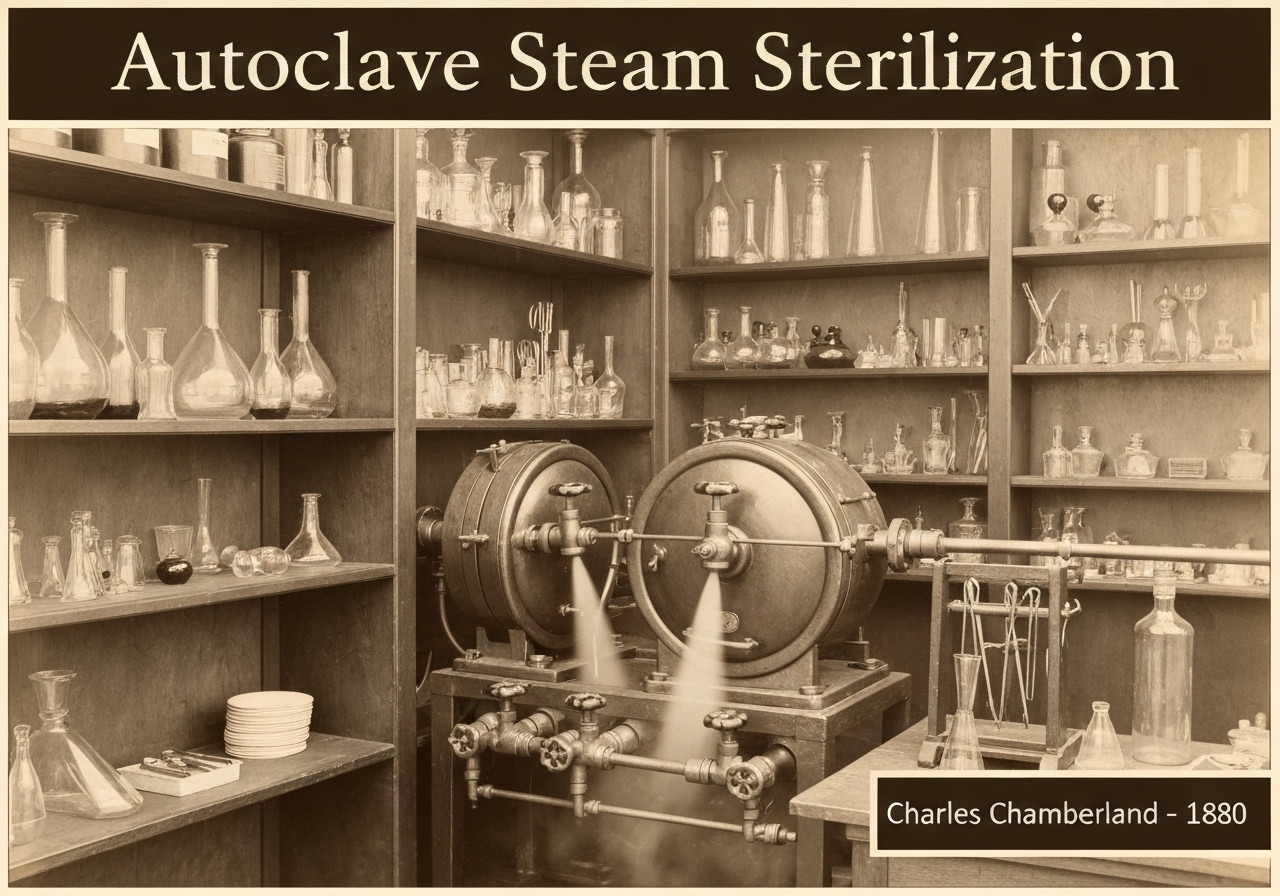

A 方法 using high-pressure saturated steam at high temperatures to sterilize equipment and supplies. A typical cycle is 121 °C (250 °F) at 100 kPa (15 psi) above atmospheric 压力 for 15 minutes. This combination of heat and moisture effectively denatures proteins and enzymes, killing all microorganisms, including resilient bacterial spores.

The autoclave’s effectiveness stems from the principles of thermodynamics and microbiology. Unlike dry heat, which kills microorganisms through slow oxidation, moist heat from saturated steam is far more efficient. The steam transfers heat energy rapidly and upon contact with a cooler surface, it condenses, releasing its latent heat of vaporization. This process causes a rapid and irreversible coagulation and denaturation of essential proteins, enzymes, and nucleic acids within the microbial cells, leading to their death. The increased pressure inside the autoclave serves a critical purpose: it raises the boiling point of water. At standard atmospheric pressure, water boils at 100 °C, a temperature insufficient to reliably kill bacterial endospores, which are highly resistant dormant structures. By increasing the pressure to approximately 15 psi (100 kPa) above atmospheric pressure, the boiling point is elevated to 121 °C. This higher temperature, combined with the penetrating power of steam, ensures the destruction of even the most resilient spores, such as those from Geobacillus stearothermophilus, which is often used as a biological indicator to validate autoclave performance. The typical 15-minute cycle time at 121 °C is a standard derived from thermal death time studies, providing a significant safety margin to achieve a high 无菌保证级别 (SAL). The process is not suitable for heat-sensitive materials like 塑料 or delicate electronics, which would be damaged by the high temperatures and pressure.

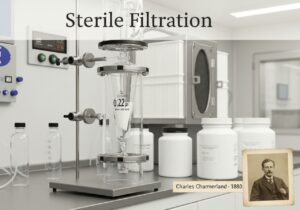

Historically, the autoclave was a direct descendant of the ‘steam digester,’ a pressure cooker invented by Denis Papin in 1679. However, its application to microbiology was pioneered by Charles Chamberland, a collaborator of Louis Pasteur, in 1879. Working in Pasteur’s lab, Chamberland recognized the need for a reliable method to sterilize culture media and equipment to support the burgeoning field of bacteriology and validate the germ theory of disease. His invention provided the first robust tool to eliminate all forms of microbial life, revolutionizing experimental biology, medicine, and surgery. It allowed for the preparation of sterile culture media, enabling the isolation and study of pure bacterial cultures, a cornerstone of modern microbiology established by Robert Koch. The autoclave’s introduction into clinical practice dramatically reduced surgical site infections and made complex surgeries safer, becoming an indispensable tool in hospitals worldwide.