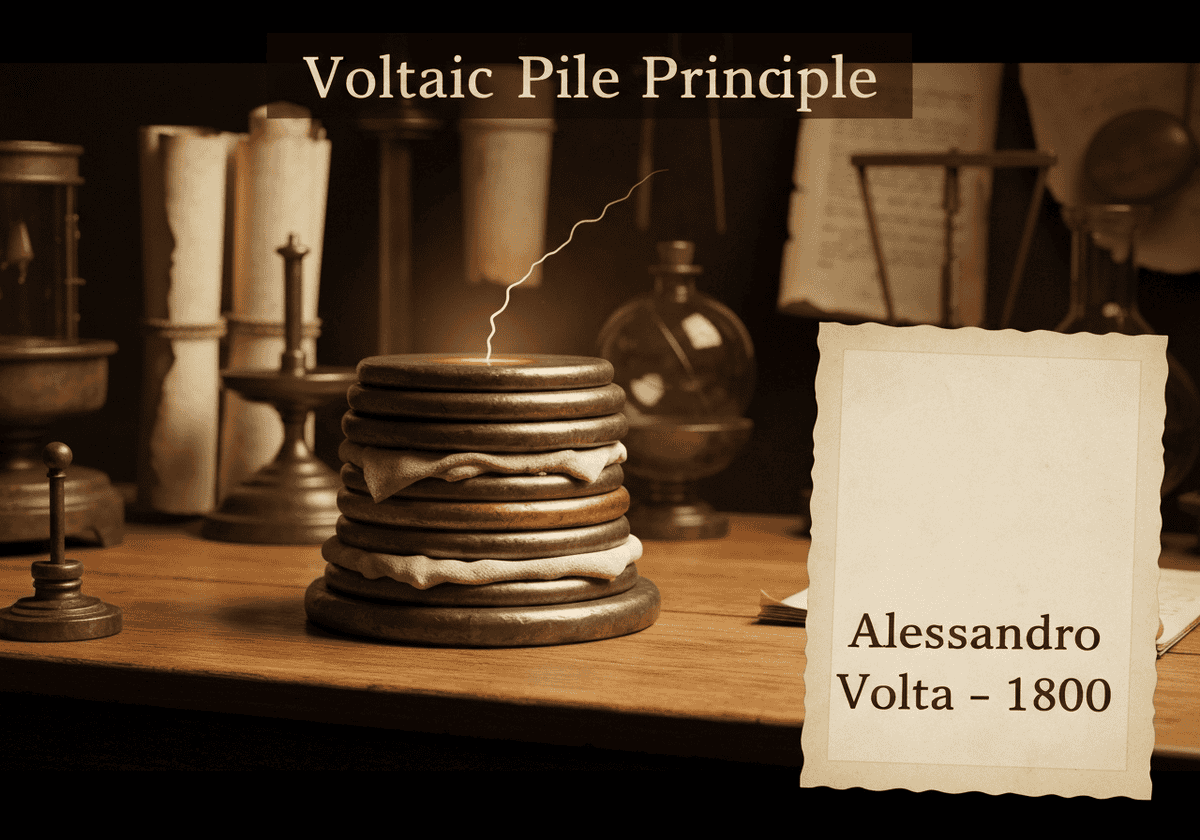

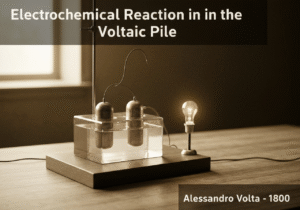

The first electric battery, it produces a direct current by stacking pairs of dissimilar metal discs (e.g., zinc and copper) separated by brine-soaked cloth. Each pair forms a galvanic cell, and stacking them in series increases the overall voltage. This arrangement demonstrated the first continuous conversion of chemical energy into electrical energy, paving the way for modern electrochemistry.

The Voltaic pile operates on the fundamental principle of the electrochemical series. When two different metals, like zinc and copper, are connected by an electrolyte (in this case, brine-soaked paper), an electrochemical reaction occurs. Zinc, being more reactive, readily oxidizes, losing electrons and forming zinc ions that dissolve into the electrolyte. These electrons travel through the external metallic path to the copper disc. At the copper surface, a reduction reaction occurs; typically, hydrogen ions from the water in the electrolyte accept the electrons to form hydrogen gas. This flow of electrons constitutes an electric current.

Each zinc-copper pair, separated by the electrolyte, is a single ‘cell’ that produces a small voltage (around 0.76 volts). The genius of Volta’s design was stacking these cells in series. By placing them one on top of another (copper, zinc, brine-soaked cloth, copper, zinc, etc.), the voltages of the individual cells add up. A pile with 20 cells could produce about 15 volts. This was the first device to provide a steady, continuous source of electric current, unlike the static discharges from Leyden jars.

However, the Voltaic pile had significant limitations. The hydrogen gas produced at the copper electrode would form a layer of bubbles, insulating the electrode from the electrolyte. This phenomenon, known as polarization, quickly increased the internal resistance and caused the voltage to drop. Additionally, the electrolyte would leak and evaporate, and local short-circuits could occur, limiting its practical lifespan.