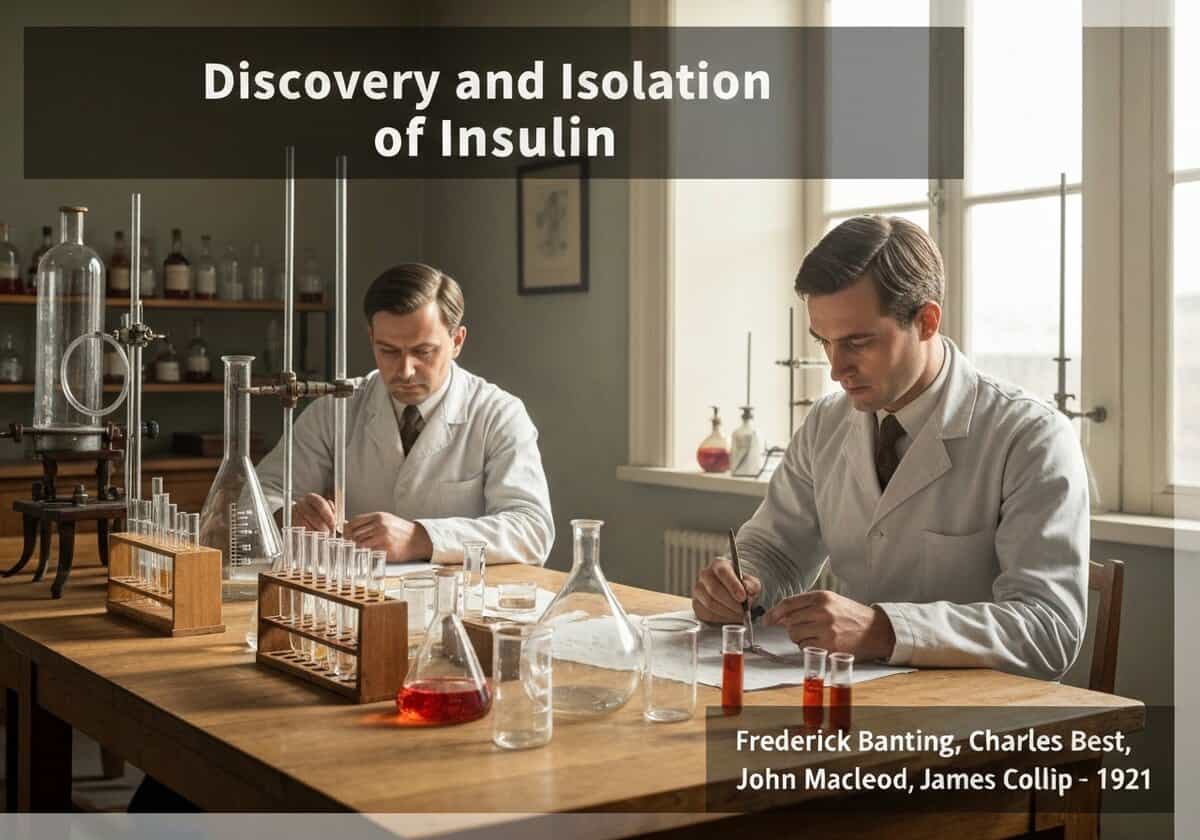

In 1921, Frederick Banting and Charles Best, under John Macleod’s direction at the University of Toronto, isolated insulin from canine pancreatic extracts. Biochemist James Collip then developed a purification process, making the extract safe for human use. This discovery transformed type 1 diabetes from a fatal disease into a manageable condition, earning Banting and Macleod the 1923 Nobel Prize.

Before 1921, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes was a death sentence, often within months. The prevailing theory, proposed by researchers like Oskar Minkowski and Joseph von Mering in 1889, linked the pancreas to diabetes by showing that its removal in dogs induced the disease. The challenge was to isolate the specific anti-diabetic substance from the pancreas without it being destroyed by the organ’s own digestive enzymes. Frederick Banting, a young surgeon, hypothesized that ligating the pancreatic ducts would cause the enzyme-producing acinar cells to atrophy, leaving the islets of Langerhans, which he believed produced the sought-after secretion, intact. He proposed this idea to John Macleod, a prominent physiologist at the University of Toronto. Macleod was initially skeptical but provided Banting with lab space, ten dogs, and the assistance of a medical student, Charles Best. Over the summer of 1921, they successfully induced diabetes in dogs by removing their pancreas and then treated them with an extract from the degenerated pancreases of duct-ligated dogs. The extract, which they called “isletin,” effectively lowered blood glucose levels. The next crucial step was purification. Biochemist James Collip joined the team and developed a 方法 using alcohol extraction to produce a purer, less toxic form of the extract suitable for human trials. The first human patient, 14-year-old Leonard Thompson, was successfully treated in January 1922, marking a turning point in medical history.